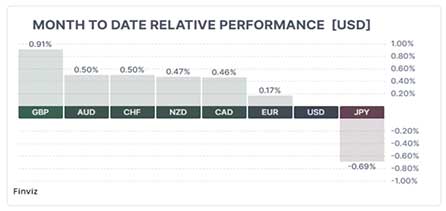

The U.S. jobs market remains robust, and uncertainty surrounding tariffs is causing the Federal Reserve to pause its actions. Meanwhile, most G10 central banks, except the Bank of Japan, are likely to cut rates before the Fed resumes easing. This should theoretically strengthen the USD against major currencies, yet the USD continues to weaken.

Central banks control short-term interest rates, but long-term rates are market-driven, influenced by expectations of future central bank policies, inflation, and the supply and demand for Treasury debt. President Trump aimed to lower long-term interest rates by reducing the deficit, which affects the long-term premium. However, his “Big Beautiful Bill,” passed by the House on May 22, 2025, is projected to increase federal spending and extend tax cuts, potentially adding $2.5 trillion to $5.2 trillion to the national debt over the next decade, according to estimates from the Congressional Budget Office and the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Coupled with a $4 trillion debt ceiling increase, this could exacerbate the U.S.’s “unsustainable fiscal path,” putting further strain on the $36.8 trillion national debt. Persistent warnings suggest future risks of higher taxes or increased money printing, potentially leading bond buyers to demand higher yields.

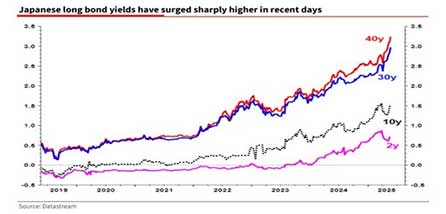

In Japan, the bond market is facing challenges, with 40-year Japanese Government Bond (JGB) yields rising to nearly 3.7%, up a full percentage point since April. Japan’s chronic debt issues are well-documented, with its credit rating three notches below the U.S. despite the U.S.’s recent downgrade. Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba has described Japan’s fiscal situation as worse than Greece’s during its debt crisis. This is not new information.

The key implication for the U.S. is that rising JGB yields could impact Treasurys. Japanese investors, who previously sought higher yields abroad due to the Bank of Japan’s suppression of domestic bond yields, may now find JGBs more attractive. With their liabilities in yen, they might reduce exposure to U.S. Treasurys, avoiding currency risk. This shift could signal declining foreign participation in the U.S. Treasury market, potentially amplified by increased U.S. debt issuance from the “Big Beautiful Bill.”

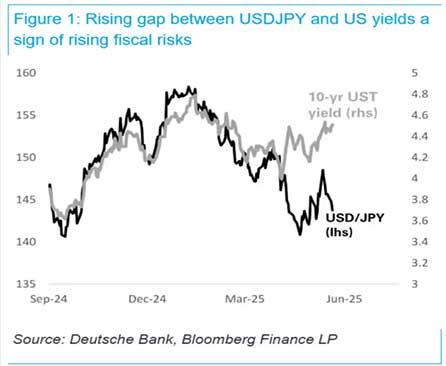

Despite rising Japanese bond yields, the yen is strengthening, not weakening, which contradicts expectations if Japan’s debt burden were the sole driver. The traditional correlation between USD/JPY and U.S. Treasury yields has weakened, suggesting U.S. fiscal risks may be growing. A widening gap between U.S. Treasury yields and USD/JPY could be a critical indicator of these risks.

Is a U.S. debt crisis imminent? It’s possible, especially with Trump’s tariffs and the “Big Beautiful Bill” likely to fuel inflation and deficits. The recent 40-basis-point rise in the implied overnight rate in Fed funds futures could explain higher long-term rates. However, a debt crisis need not be catastrophic if it forces Washington to adopt a credible, sustainable fiscal policy. The Treasury could manage long-term yields by financing more of the deficit with Treasury bills, as Janet Yellen did in November 2023, a form of Yield Curve Control. In a severe crisis, the Fed could resume Quantitative Easing to provide liquidity. The U.S. is unlikely to go bankrupt, as it can print dollars to pay debts, but this could erode confidence, making assets like gold and bitcoin more attractive.

I’ll leave you with another gem from Peter Mallouk. He’s a great follow.