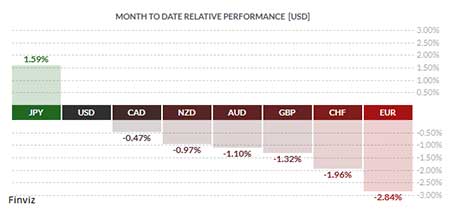

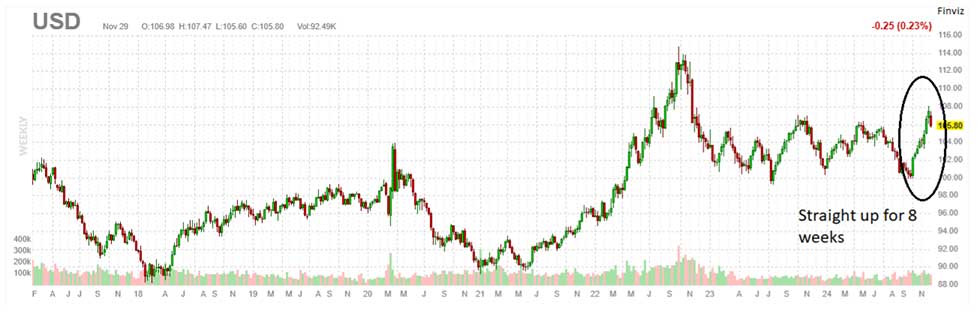

The broad based USD, represented by the US dollar index has been up only since September 30th. It has been up for 8 straight weeks until last week. When the USD is up only it gets reffered to a “wrecking ball” and for good reason, it can have profound, often negative, effects on global economic stability, akin to a wrecking ball swinging through international financial structures. The term “wrecking ball” metaphorically suggests that while the USD’s strength might seem beneficial or stabilizing in the context of American economic policy or as a safe-haven asset, its relentless rise can have profound, often negative, effects on global economic stability, akin to a wrecking ball swinging through international financial structures. It encapsulates several economic and geopolitical implications that are seen as potentially destructive or destabilizing:

- Global Economic Imbalance: A stronger USD can make imports cheaper for Americans but more expensive for countries with weaker currencies. This can lead to a reduction in global trade as other countries might find their exports to the US less competitive. This imbalance can disrupt economies that rely heavily on exports to the US, potentially leading to economic downturns or recessions in those regions.

- Debt and Borrowing Costs: Many countries, companies, and even individuals have debts denominated in USD. When the dollar strengthens, the real value of these debts increases, making repayment more burdensome. This can lead to defaults, especially in emerging markets, where the ability to earn USD might not keep pace with the dollar’s appreciation.

- Currency Devaluation: A rising USD often leads to the devaluation of other currencies. This can trigger competitive devaluations as countries try to maintain their export competitiveness, which can lead to currency wars. Such scenarios can destabilize international financial systems.

- Capital Flows: A strong dollar can attract capital flows into the US, seeking safety or better returns. This can lead to a ‘hot money’ problem where capital flows in and out of countries rapidly, causing financial instability. Countries might experience sudden capital outflows, leading to financial crises.

- Monetary Policy Constraints: Countries might find their monetary policies constrained. For instance, if they peg their currency to the USD or if they’re trying to manage inflation, a strong dollar might force them into tighter monetary policies, which could stifle economic growth.

- Geopolitical Power Shifts: The USD’s role as the world’s reserve currency gives the US significant geopolitical leverage. A stronger USD can be seen as an assertion of this power, potentially leading to resentment or efforts by other countries to reduce their reliance on the USD, which might involve creating alternative financial systems or currencies.

- Inflation and Deflation Risks: Domestically, a strong dollar can lead to deflationary pressures in the US due to cheaper imports, which might be good for consumers in the short term but can lead to economic stagnation if prolonged. Conversely, for countries with weaker currencies, it can exacerbate inflation as import costs rise.

- Investment and Market Sentiment: A continuously strengthening dollar can affect global investment strategies, potentially leading to a bubble in dollar-denominated assets. When this trend reverses, it could lead to significant market corrections or crashes.

While the Fed initiated its rate-cutting cycle with a 50 bps reduction, the market initially assumed this would lead to a series of smaller cuts. However, current data has sparked debates over whether the next meeting will result in a cut, a pause, or a skip. This uncertainty has fueled the “USD wrecking ball” thesis, as sustained high rates could continue boosting the USD.

Even if the Fed pauses, liquidity measures could cap further USD strength by providing a “put” on liquidity support.

President-elect Trump’s proposed trade tariffs — 60% on China and 10-20% on other countries — add another layer of complexity. Tariffs could be inflationary, limiting the Fed’s ability to cut rates, thus supporting a stronger USD. However, these tariffs may be negotiation tools rather than punitive measures, offering a silver lining.

During Trump’s first term, his tax cuts and tariffs did not significantly spur inflation. Both Trump and JD Vance have advocated for a weaker USD to boost U.S. manufacturing and competitiveness.

The recent nomination of Scott Bessent as Treasury Secretary has calmed some fears. Analysts, including Thierry Wizman from Macquarie, believe this signals a more transactional, less inflationary approach to tariffs. The market now anticipates a focus on spending and tax cuts rather than aggressive trade policies.

In sum, Bessent’s appointment and a possible change to support liquidity developments by the Fed may by the medicine needed to curve USD strength.