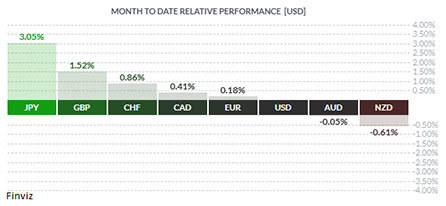

The Japanese yen was the top-performing currency in February, appreciating by 3.05% due to a combination of rising Japanese interest rates and a decline in U.S. 10-year interest rates.

As illustrated in the chart above, the USD weakened against the yen, dropping from approximately 159 in early January to around 148.55 by the last week of February—its lowest level since October. This yen strength is attributed to expectations that the Bank of Japan will continue normalizing monetary policy following decades of negative interest rates. Japan’s January CPI stood at 4%, surpassing the U.S. inflation rate of 3%—a phenomenon last observed in 1997-1998. While market surveys indicate a preference for a July interest rate hike, the swaps market does not fully price in the next increase until early Q4.

Conversely, the New Zealand dollar was the weakest among major currencies in February. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand lowered its benchmark interest rate by 50 basis points to 3.75% in an effort to stimulate the economy amid moderating inflation. Governor Adrian Orr signaled the likelihood of further rate cuts, projecting a decline to approximately 3% by year-end.

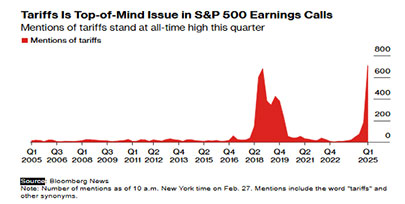

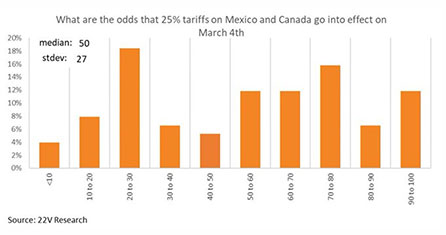

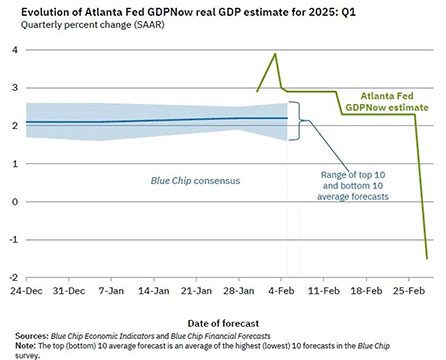

Turning to the USD Index—a measure of the dollar against a basket of major currencies—it surged nearly 10% between late September and mid-January, peaking on January 13, just a week before President Trump’s inauguration. However, profit-taking ensued, and despite indications in early February that 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico were imminent, the index failed to reach new highs. The index subsequently declined by about 3.6% from its January peak as markets perceived the tariffs as a negotiating tactic.

As February came to an end, Trump reaffirmed his intention to impose the 25% tariff on Mexico and Canada (excluding energy), introduced an additional 10% tariff on China, and signaled the possibility of further tariffs on the EU and specific industries—such as steel, aluminum, copper, autos, semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, and lumber. Consequently, the USD Index rebounded, ending the month on a strong note and hitting a two-week high on the final trading day.