Setting the Stage

At the beginning of July, I was contemplating how Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell would set the stage at the FOMC meeting on July 31st for a potential rate cut in September, without causing a significant rally in the equity markets or triggering a new wave of easing in financial conditions. At the time, I was unaware that two other factors would dampen the market’s response to the FOMC meeting’s narrative shift.

The FOMC statement and Powell’s press conference confirmed the market’s expectations that the Fed would begin an easing cycle at its next meeting in September. Surprisingly, Powell acknowledged that there had been discussions about cutting rates at the meeting but managed to temper this admission by clarifying that there was no consideration of a 50-basis-point cut in September.

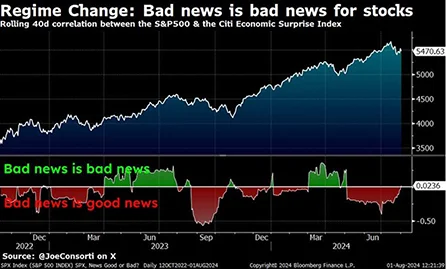

Despite the Fed meeting the market’s expectations, equity markets did not rally as anticipated due to two key factors. The first factor occurred before the Fed meeting and received less attention. The second factor was related to economic data, specifically the ISM data and the employment report.

Economic Data

The economic data released was concerning. The day after the FOMC meeting, a measure of U.S. manufacturing activity fell to an eight-month low in July. The US ISM manufacturing index dropped to 46.8 from 48.5, marking its fourth consecutive monthly decline. More significantly, the employment component hit its lowest level since 2020, just ahead of the release of the employment report the following day.

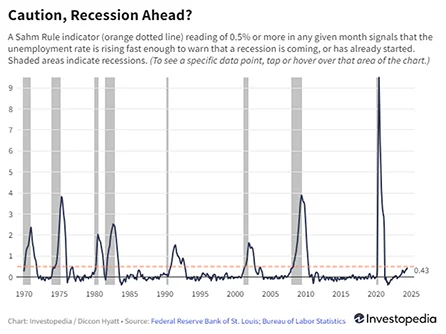

Friday’s U.S. jobs report revealed that the economy added only 114,000 jobs, down from 206,000 in June and well below the expected 175,000. Moreover, the unemployment rate rose to 4.3%, higher than the anticipated 4.1%, triggering the Sahm Rule. This rule is a recession indicator suggesting that a recession is likely if the three-month moving average of the unemployment rate increases by half a percentage point from its lowest point in the previous 12 months. Claudia Sahm, a former Fed economist and the creator of this indicator, commented that while the U.S. isn’t in a recession yet, “we’re not headed in a good direction.”

As expected, this led to the worst day in the U.S. stock market since the COVID-19 acknowledgment on March 16, 2020, as the market speculated that the Fed was behind the curve.

The Yen Carry Trade

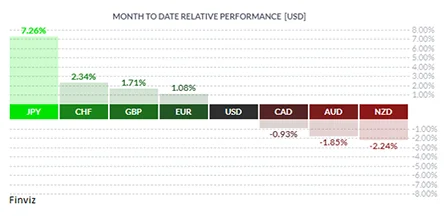

While the poor economic data was significant, I believe the primary driver of the market’s sentiment was the beginning of the unwind in the yen carry trade. As seen in the chart, the USD peaked against the yen on July 11th, making the yen the best-performing currency in July with a 7.6% gain—a substantial move in the currency market. This was when the market recognized that the Bank of Japan was likely to change its policy, necessitating a reassessment of carry trades. The stock market also peaked around that time.

Just hours before the FOMC meeting, the Bank of Japan made a notable move by raising interest rates by 15 basis points to their highest level in 15 years. This was the largest hike since 2007 and followed the BOJ’s decision to end eight years of negative interest rates. Governor Kazuo Ueda did not rule out another hike this year and emphasized the bank’s readiness to continue raising borrowing costs to levels deemed neutral for the economy.

With the BOJ raising rates at a time when other central banks are beginning to cut, the pressure on the carry trade increases. The carry trade has been a feature of the yen trade for about 30 years, allowing investors to borrow in yen at low or zero interest rates and reinvest the proceeds in currencies with higher returns. Investors would borrow in yen, buy USD, and invest in bonds and stocks. Now, this process is beginning to reverse. While it is challenging to determine the exact amount of global positions in yen-funded carry trades, it is estimated to be around $3 trillion.

The long-anticipated turn in the USD seems imminent. The Fed is preparing to start a rate-cutting cycle, and the notorious yen carry trade is beginning to unwind. The two-pronged policy mix—loose fiscal and tight monetary policy—that has driven the USD’s rally in recent years is coming to an end, just as the economy slows and inflation subsides. While a new U.S. President or Congress is unlikely to address the fiscal spending issue, what is changing is monetary policy. Consequently, the USD is expected to begin its decline